I have a theory about why Margaret Atwood wrote Oryx & Crake and The Year of the Flood, and may—if certain rumors be true—be at work on a third novel in the series.

But first, let me address the hisses and catcalls from the back. Yes you, over there.

Many of my hardcore SF friends dismissed Oryx & Crake, and never read The Year of the Flood, on principle. Their objections were along the lines of, “That’s all been done before by real SF writers. Oh—and it’s been done better. Much better.” Some have been blunt: “She’s a rip-off artist.”

To my hardcore SF friends and those who agree wholeheartedly with them let me say, You may be right. And—here—in this post—I’d like to explore another issue and present a theory that transcends Margaret the author and these two novels. I’m hoping you’ll stick around to hear it.

I hope, too, I can—at least for the duration of this post—ask any die hard Atwood-is-a-witch-burn-her! readers to put aside the contentious issue as to whether Oryx & Crake and The Year of the Flood are “SF” or “speculative fiction.”

(I can see Monty Python taking this and running with it: “Tastes great!” / “Less filling!” morphing into “SF!”/”Speculative fiction!”)

Truth in lending: I am a big, big Atwood fan. Cat’s Eye and The Blind Assassin are two of my favorite novels of all time—re-read often—and Moral Disorder one of my favorite collections of short stories. I think I’m close to owning just about everything Atwood’s published, including such oddities as Days of the Rebels 1815-1870 and Strange Things: The Malevolent North in Canadian Literature.

So—

My thought begins with Atwood as a writer of literature, and ends with Atwood as the writer of Oryx & Crake and The Year of the Flood.

That Atwood is a serious writer is easily demonstrated: she was nominated for the Man Booker International Prize twice (2005, 2007), was shortlisted for the Booker Prize four times (The Handmaid’s Tale, Cat’s Eye, Alias Grace, and Oryx & Crake), and won the Booker for The Blind Assassin in 2000. The Cambridge Companion to Margaret Atwood was published in 2006.

This begs the thought: why would a serious writer of literature write Oryx & Crake and The Year of the Flood? Call them SF or speculative fiction, they veer towards genres serious writers often avoid, and serious critics ignore or pan.

I began to develop an answer when listening to Atwood’s CBC Massey Lectures (now gathered together in Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth). I was struck by a comment she made about why writers write.

Why do writers write?

Because writers see how the story ends.

We all know folks—many of whom are family and friends—who can’t see how the story ends, especially the story of their own lives. Like locomotive trains racing towards a collapsed bridge, they speed along, oblivious to what’s right there in front of their noses. “Jump!” we scream, but they don’t listen, ask us to pipe down, suggest we respect their boundaries and butt out, or remark, snidely, with something like, “Look who’s calling the kettle black.” On they go, and down the train goes into the chasm. Boom.

Writers then, if we stick with this thought, see lots of “ends” and jot them down, perhaps in the vain hope we readers will learn to see ends too and not plummet to our deaths, metaphorical and real.

There is, of course, a larger story out there: the story of the human race.

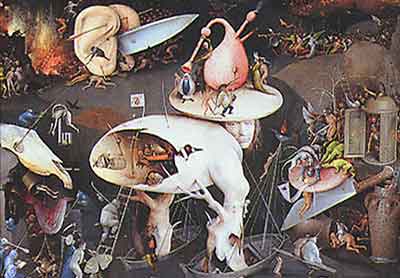

If Act I was all of us, not so long ago, living relatively non-destructively on the earth, Act II—during which obstacles of increasing difficulty arise, testing our heroic skills and resolve more and more—is well underway.

We appear to have escaped massive destruction from an all out war between the country formerly known as the U.S.S.R. and the U.S.—thought who knows what the future may hold—but now international terrorism and climate change are upon us, not to mention the “inevitability” of future plagues. In Act II the audience wonders—the higher the obstacles grow—Will the hero make it? As audience to our own future, we could ask, Will we make it?

And here we see how rampant denial is. While some prophets shout from rickety soapboxes on street corners, most folks ignore them. “You’re rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic!” the prophets scream, hoarser now. Many wonder if these folks have forgotten to take their medications.

Let’s assume that writers can see how the story ends.

Let’s assume, too, that the best writers see how the story ends better than most.

And let’s assume that Margaret Atwood, one of the very best writers living, has difficulty sleeping at night because her intuition about how our story ends evokes crystal-clear, Technicolor nightmares.

Perhaps—and this is my theory—Atwood said to herself, I’m feeling a bit like a crazy prophet and I’ve got a pretty good soap box here—maybe I should start shouting—just maybe some of those folks who dig my literary stuff will get the message. (SF fans can pat themselves on the back here as they’ve presumably known we’re all going to hell in a hand basket.)

Another way of looking at this might be: what’s a writer’s reputation worth if civilization goes up in smoke—or sinks to its knees, the Black Plague back with a vengeance. Perhaps Atwood has chosen to “risk” her “stellar” reputation by “coming down” and writing Oryx & Crake and The Year of the Flood. (And here SF fans can pat themselves on the back again, for here we see the undeniable value of fiction, whether we call it “science” or “speculative” fiction.)

Perhaps Atwood’s doing everything she can to help get the human oil tanker back on course before it hits the rocks, bursts open, bursts into flame. What she’s doing—”risking her reputation”—makes no sense if your timeline only extends to the next literature prize, or even “my reputation after I’m gone.” It makes a lot of sense if your timeline is a bit longer. Not too many people were reading books in Oryx & Crake and The Year of the Flood; no mention was made of literature prizes in that future.

Still putting aside the contentious issues of who painted this kind of future first and who did it better, Atwood’s research for both Oryx & Crake and The Year of the Flood was extensive. I am reminded, almost daily, of how many “cutting edge” technologies referenced in both novels are already in full development, already out there, and out of control. SF has become speculative fiction has become reality quickly.

So where does this theory leave us?

If I’m right, I believe it presents writers with a challenge: if part of who I am is my ability to see the end of the story and to tell that story, am I living up to that precious gift? Am I looking as I ought, as I am capable? Am I telling the stories that matter? Am I living for short-term story—quick success—or the really big win—our survival?

Readers are challenged too: do we choose to read the small stories, the tall tales? Or do we choose to read the stories that matter, that change minds, transform. And to recommend them to other readers.

As creatures with monkey brains—to borrow a phrase right out of Oryx & Crake—do we strive to be chief monkey while Rome burns—or the Titanic goes down—or the unmonitored corporations take over? Or do we turn our gifts and strengths towards other challenges.

The biggest challenge, of course is acting when the immensity of the problem is so overwhelming.

Here, I feel, Atwood provides direction: you do what you can, based on who you are and where you are situated in life. If you’re a Booker Prize winning novelist, you use that position to paint an end-of-the-story picture. If you’re you, or me, you look around and do the same with the bits and pieces of your own life.

That’s all we can do.

And it is something, rather than nothing.

So spread the word.

Tell the story—so we can rearrange the deckchairs on a starship on a mission of endless discovery.

Dr. Kirtland C. Peterson—”Cat” to his friends and colleagues—feeds his left brain with science, his right brain with the rich feast of fiction, including SF and fantasy.

Among his life’s highlights are sitting in the pilot’s seat of a shuttle prepping for launch at the Kennedy Space Center, and accepting Brannon Braga’s invitation to pitch Star Trek scripts at Paramount in LA.

Recently finished The Hobbit (read most marvelously by Rob Inglis), Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wave in the Mind: Talks & Essays on The Writer, The Reader & The Imagination, and Alice Munro’s The View from Castle Rock. Just started J.R.R. Tolkein’s The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays.